In early 2020, CHBC, along with almost every other church in the world, was forced to contend with the opening days of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time Caleb Morell was working as Pastor Mark Dever’s personal assistant. Dever tasked him with finding out how the church had responded to the Spanish flu epidemic a century prior. ]]>

In early 2020, CHBC, along with almost every other church in the world, was forced to contend with the opening days of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time Caleb Morell was working as Pastor Mark Dever’s personal assistant. Dever tasked him with finding out how the church had responded to the Spanish flu epidemic a century prior. ]]>

I love a good biography. It’s always fascinating and often inspiring to read the account of a life of special significance. Yet for all the biographies I’ve read, A Light on the Hill may be the first whose subject was not a person but a church. It surprised me what a blessing it was to read about that church and to see how God has seen fit to bless, preserve, and use it for so many years.

In late 1867, Celestia Anne Ferris, a young member of E Street Baptist Church in Washington, called her friends together to pray for the establishment of a church on Capitol Hill. Only a few people were present that evening and their specific prayers were not recorded, but it did not take long for God to begin to answer them. By 1871, they began a Sunday school in a rented building and by 1874 they were ready to purchase property and associate together as the Metropolitan Baptist Association. On February 6, 1876, nine years after their first prayer meeting, they dedicated a new chapel to the Lord—a chapel called Metropolitan Baptist Church. Though the building was later demolished in order to make way for a larger one and though its name has changed a couple of times, the church has remained ever since. Today it is known as Capitol Hill Baptist Church.

In early 2020, CHBC, along with almost every other church in the world, was forced to contend with the opening days of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time Caleb Morell was working as Pastor Mark Dever’s personal assistant. Dever tasked him with finding out how the church had responded to the Spanish flu epidemic a century prior. Morell began to rummage “through the dusty pages of minutes, stored in filing cabinets in a basement closet underneath the baptistry.” As he did so, he “began to reconstruct the events of 1918 that led the church to cancel services for three weeks in response to the onset of the Spanish flu.” A few days later, he published the story at 9Marks.org and gained an overwhelming response that extended to the mainstream media. “I began to experience the firsthand impact narrative history can have on current events: to draw needed light from the past to put present challenges in perspective. For the next months, I spent any spare time poring over newspaper clippings and members’ meeting minutes.”

This study led to a class on CHBC’s history and, eventually, to this book. And what a book it is. While the great majority of the people who attended CHBC over the years were as ordinary as you and me, it has been home to a few outsized personalities. Through them and its strategic location, it has been able to have a significant impact on evangelicalism within the United States and beyond. In his foreword, Mark Dever highlights a few of the noteworthy people: “Joseph Parker, the abolitionist pastor who argued with Lincoln in person; Agnes Shankle, the faithful member who stood up to the pulpit search committee and perhaps, thereby, saved the congregation from liberal compromise; K. Owen White, the reforming expositor who later gained fame for a question he asked Senator John F. Kennedy when he ran for president. So packed with characters is this story that not all of these tasty details could be included. But there are so many more stories and so many interesting characters.”

There is the first African-American member who persevered through many challenges because she loved the Lord, loved the church, and loved its worship. There are the reforming pastors who pulled the church back from the brink of compromise. There is Carl F.H. Henry who was the founding editor of Christianity Today. There is the fallen leader who risked destroying the church even as he destroyed his own ministry, and tied closely to him, the godly man whose wife was victimized but who endured and forgave for a higher cause. There are those and so many others.

As he comes to the end of the book, Morell considers how the church remained centered on the gospel and rooted in its local community for 150 years. He offers a three-part answer: Pastors who preached the gospel, members who lived lives of quiet faithfulness, and a congregation that prayed. “Through the faithful preaching of the word, the selfless labors of godly members, and the prayers of God’s people, God has preserved a brightly shining beacon for the gospel on Capitol Hill.” May he continue to do so for another 150 years and far beyond.

]]> I am not aware of a verse in the Bible that says every Christian must read at least one biography of Charles Spurgeon. Or every Calvinist, at least. But I also wouldn’t be completely shocked if it’s there somewhere and I’ve just missed it. And that’s because his life and ministry were powerfully unique in so many ways.]]>

I am not aware of a verse in the Bible that says every Christian must read at least one biography of Charles Spurgeon. Or every Calvinist, at least. But I also wouldn’t be completely shocked if it’s there somewhere and I’ve just missed it. And that’s because his life and ministry were powerfully unique in so many ways.]]>

I am not aware of a verse in the Bible that says every Christian must read at least one biography of Charles Spurgeon. Or every Calvinist, at least. But I also wouldn’t be completely shocked if it’s there somewhere and I’ve just missed it. And that’s because his life and ministry were powerfully unique in so many ways.

I have often thought that the word “unique” is overused today. After all, if the word applies to everything, it actually applies to nothing. It’s not possible for everything to be unique, is it? Yet there are a handful of figures in history for whom the word fits, and Spurgeon is most definitely among them. In so many ways he really was one-of-a-kind. He was one-of-a-kind in the reach of his preaching ministry, in the power of it, and in its impact. He was one-of-a-kind at the young age at which he became famous for his preaching and his ability to remain untainted by the adulation. He was one-of-a-kind in the sheer output of his tongue and pen. I dare say he was one-of-a-kind in all the ways he was one-of-a-kind, unique for all the ways he was unique.

Every biography of Spurgeon tries to figure out why his ministry was so uniquely blessed by the Lord. It examines his background, considers his early influences and education, remarks on the godliness of his parents, dissects his preaching, and so on. But in the end, I don’t think any of this gets us a whole lot closer to a satisfying answer. After all, lots of people were raised in the way Spurgeon was raised. Many were exposed to the theologians he was exposed to and were influenced by similarly godly parents and mentors. Yet their reach was not nearly so wide and their impact not nearly so great. It seems to me we do best to leave the matter in the hands of the Lord and simply marvel at what he chose to accomplish through this one man—a man he so clearly baptized with a special kind of charisma, intellect, skill, influence, and power.

Spurgeon is the subject of a host of biographies including an excellent new one by Alex DiPrima titled simply Spurgeon: A Life. Any biographer of a man as unique as Spurgeon has to make a formative decision: Will this account of the subject’s life be concise or exhaustive? When it comes to Spurgeon, there would be enough material and enough interesting themes to fill multiple volumes, yet few people are interested in reading that much. I think DiPrima struck a good balance in capping his book at around 300 pages. That is enough to account for the most prominent events of Spurgeon’s life and to introduce the most important characters, but not so much that it grows tiresome. It’s enough that he can explain what Spurgeon believed yet without writing what could essentially be a volume of theology. It’s just right.

I trust that many who are sticking with me this far into the article have already read at least one biography of Spurgeon. If not, there is no better place to begin than with this one. And if you have, I still think you’ll benefit from it. It is longer than a few, shorter than many, and more updated than them all. I am sure you’ll be blessed as you read how the Lord so magnificently glorified himself through a man who was and remains truly unique.

Here are a few recommended biographies:

- Spurgeon: A Life by Alex DiPrima. The most updated.

- Spurgeon: A Biography by Arnold Dallimore. A classic.

- The Forgotten Spurgeon by Iain Murray. A can’t-go-wrong biographer.

- Susie: The Life and Legacy of Susannah Spurgeon, wife of Charles H. Spurgeon by Ray Rhodes Jr. A look at Susie’s influence on her husband.

- Spurgeon: Prince of Preachers by Lewis Drummond. Longer than the others but a bit dated in its scholarship and, according to DiPrima, repeating some errors from older works.

- Living by Revealed Truth by Tom Nettles. The best long option.

- Charles Spurgeon: Prince of Preachers. One for younger readers.

The United States has produced more than its fair share of fascinating figures. Over the course of its storied history, it has produced a host of figures who have shaped the nation, the continent, and the world. Many of these have been its presidents and politicians, though others have been its inventors, its business leaders, or those who have in other ways shaped public morality. While each of these ]]>

The United States has produced more than its fair share of fascinating figures. Over the course of its storied history, it has produced a host of figures who have shaped the nation, the continent, and the world. Many of these have been its presidents and politicians, though others have been its inventors, its business leaders, or those who have in other ways shaped public morality. While each of these ]]>

The United States has produced more than its fair share of fascinating figures. Over the course of its storied history, it has produced a host of figures who have shaped the nation, the continent, and the world. Many of these have been its presidents and politicians, though others have been its inventors, its business leaders, or those who have in other ways shaped public morality. While each of these people has a public side, they also have a private side. And sometimes people who make a great impact publicly can live with great immorality privately.

In the late 1990s, the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal compelled Marvin Olasky to begin thinking about the effect private activities have on the lives of public leaders. In the context of that scandal, the White House insisted that Clinton’s private immorality had no bearing on his public role. The voting public seemed to agree that the two could remain neatly compartmentalized. “Many journalists at the time agreed with Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen that a president ‘conventionally immoral in his personal life’ can still be a wonderful ‘person in his public life.’ Can be, sure, because life is complicated. But how likely is that?”

Olasky examined the issue in his 1998 book The American Leadership Tradition. But time showed that perhaps he over-corrected—that while many conventional journalists oversimplified by taking the “no effect” line, he oversimplified in the other direction. Not only that, but in his own judgment he was censorious and lacked nuance. In Moral Vision: Leadership from George Washingon to Joe Biden (which is a substantially revised and expanded edition of his former work) he takes up the issue again and does so through a series of short biographies of noteworthy Americans. “George Washington pledged in his 1789 inaugural address that ‘the foundation for national policy will be laid in the sure and immutable principles of private morality.’ I’ve tried to look at how we have followed through on that—or have not.”

He begins at the beginning, of course, with George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Both were great men in many ways, yet both had significant moral flaws: Washington was a slave owner; Jefferson was not only a slave owner but was also committed to sexual immorality. Olasky is not iconoclastic toward them, as if their statues ought to be torn down and their names erased from the history books. Yet, on the other hand, he does not wish to pretend that their public lives would remain entirely unaffected by their moral flaws.

As he moves to Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay, he grapples with the private and public lives of men who were responsible for the notorious Trail of Tears and the brutal subjugation of an entire people. Then he moves to Madame Restell who did so much to promote abortion among New Yorkers in the mid-1850s. He looks at the faith of Abraham Lincoln and whether it was consistent or inconsistent with his decision to wage total war against the South.

Grover Cleveland and John D. Rockefeller follow Lincoln, then Booker T. Washington and Ida B. Wells. As he reaches the modern era, he looks at both Roosevelts, Wilson, Truman, and Kennedy. In the postmodern era he pairs up Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich, then Donald Trump and Joe Biden. It is safe to say that he is no fan of either one of the latter two.

As Olasky comes to the end of the book, he reflects on assessing character and some of the “tells” that may distinguish people of good character from those of poor character. He believes that fidelity in marriage is an important one, though not the only one. He highlights others as well—following through on promises, a concern for other people, honesty, and self-discipline. He even buzzes through the Ten Commandments to see which of them, when violated, has troubled the American people and which has not. In the end, he hopes that the book causes voters to consider not only a candidate’s positions or promises but also his character.

If this book has one practical benefit, I hope it will make groups reluctant to hand out voter guides that merely list candidate votes on particular issues, as if that should be the sole determinant in casting a ballot. This does a disservice to those looking for guidance. If I have done a disservice to readers by being less emphatic on some questions than I was in the first edition, so be it. I’m more aware of the complications of history and biography than I was twenty-five years ago, but I still believe in the centrality of moral vision, which is the sum of character, experience, and faith.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading Moral Vision. Olasky is a talented writer whose work reminds me a great deal of David McCullough—about as high a compliment as I know to give. I appreciated each one of the brief biographies and was challenged by the constant focus on moral strengths and weaknesses. Some will agree and some will disagree with his conclusions, but I think all will benefit from considering them.

]]> Like a River Granger Smith Not too long ago a friend asked me, “Hey, did you hear that Granger Smith is now a student at Southern Seminary?” “No, I hadn’t heard that,” I replied. Then I surreptitiously Googled “Who is Granger Smith?” I learned that he is—or was, at least—a country music singer, and apparently a tremendously successful one. But he had chosen to leave touring behind to focus instead on becoming a pastor. It seemed like there must be a story to tell, but I didn’t think much more about it until last week when I saw a book with his name on the cover listed among Amazon’s daily Kindle deals. I bought it, read it in a day, and was glad that I did. There was, indeed, a story to tell—a story that was tragic but inspiring and encouraging. In 2019 Granger Smith was flying high. His career was booming, his albums were selling, and his fan base was building. He was filling concert halls and performing in stadiums. It was all he had ever dreamed of. And it was just then, at the height of his success, that he encountered a terrible tragedy. One day he was playing outdoors with his children when he suddenly noticed that his three-year-old son River had disappeared. He sprinted to the pool and found his son face down. Despite his efforts and the efforts of paramedics and doctors, there was nothing that could be done. River was gone. River was gone and his father soon realized…]]>

Like a River Granger Smith Not too long ago a friend asked me, “Hey, did you hear that Granger Smith is now a student at Southern Seminary?” “No, I hadn’t heard that,” I replied. Then I surreptitiously Googled “Who is Granger Smith?” I learned that he is—or was, at least—a country music singer, and apparently a tremendously successful one. But he had chosen to leave touring behind to focus instead on becoming a pastor. It seemed like there must be a story to tell, but I didn’t think much more about it until last week when I saw a book with his name on the cover listed among Amazon’s daily Kindle deals. I bought it, read it in a day, and was glad that I did. There was, indeed, a story to tell—a story that was tragic but inspiring and encouraging. In 2019 Granger Smith was flying high. His career was booming, his albums were selling, and his fan base was building. He was filling concert halls and performing in stadiums. It was all he had ever dreamed of. And it was just then, at the height of his success, that he encountered a terrible tragedy. One day he was playing outdoors with his children when he suddenly noticed that his three-year-old son River had disappeared. He sprinted to the pool and found his son face down. Despite his efforts and the efforts of paramedics and doctors, there was nothing that could be done. River was gone. River was gone and his father soon realized…]]>

Not too long ago a friend asked me, “Hey, did you hear that Granger Smith is now a student at Southern Seminary?” “No, I hadn’t heard that,” I replied. Then I surreptitiously Googled “Who is Granger Smith?” I learned that he is—or was, at least—a country music singer, and apparently a tremendously successful one. But he had chosen to leave touring behind to focus instead on becoming a pastor. It seemed like there must be a story to tell, but I didn’t think much more about it until last week when I saw a book with his name on the cover listed among Amazon’s daily Kindle deals. I bought it, read it in a day, and was glad that I did. There was, indeed, a story to tell—a story that was tragic but inspiring and encouraging.

In 2019 Granger Smith was flying high. His career was booming, his albums were selling, and his fan base was building. He was filling concert halls and performing in stadiums. It was all he had ever dreamed of. And it was just then, at the height of his success, that he encountered a terrible tragedy. One day he was playing outdoors with his children when he suddenly noticed that his three-year-old son River had disappeared. He sprinted to the pool and found his son face down. Despite his efforts and the efforts of paramedics and doctors, there was nothing that could be done. River was gone.

River was gone and his father soon realized he was not equipped to deal with such a loss. A self-professed “Dog-Tag Christian”—someone who was just Christian enough to have it stamped on his dog tags if he was a soldier being sent to war—Granger quickly turned to a rigorous regimen of self-help techniques and life on the road. “The truth is, I had no idea how to deal with this kind of pain. It broke into my world like a thief and stole my joy, my passion for life, my sanity, and it replaced them with something far more sinister: guilt.” He found some comfort in marijuana and alcohol, but only some.

It did not take long before the sorrow and guilt caught up with him. One evening, drunk and high and alone, he got within moments of taking his life. A gun was in his mouth and his finger was on the trigger when suddenly he became aware of the presence of evil around him. “There was an intruder in my presence. I was paralyzed by this new realization—I wasn’t alone in the room that night. I had been hunted, ambushed, flanked, surrounded, and put under attack by an enemy far beyond my ability to defeat.” He ripped the gun from his mouth and spontaneously cried out to Jesus. “My God, my Jesus! Save me! Save me, Jesus!” And that was the start, the prequel perhaps, of a whole new chapter in his life.

A short time later he was listening to a message by John Piper—a message about God’s love for his people—when “my eyes were opened to see things like never before. I was loved! I felt it. Not because of anything I had done. In fact, I certainly didn’t deserve it, yet He had adopted me as a son. That revelation while hearing the gospel triggered a flood—not the hopeless flood I had felt after losing River but God’s covenant flood of His Spirit to live in me and walk with me. … In that moment I was reborn! Right there in that truck on a small county road in Texas, the old me died.”

The old me had died and the new me had much different passions and desires. That transformation equipped him to come to peace with his loss and eventually led to the decision that my friend had asked me about in the opening words of this review: “Did you hear that Granger Smith is now a student at Southern Seminary?”

I will leave it to you to read Like a River and learn why and how he stepped away from touring to prepare for pastoral ministry. And I’ll leave it to you to read his reflections on God’s purposes and comforts in grief. I’ll leave it to you to read about how God blessed him and his family in the aftermath of their great loss. Whether you’ve heard of Granger Smith before now or not, and whether you know him as a multi-platinum recording artist or a Greek-memorizing seminary student, I think you’ll be blessed by reading his story.

]]> I love a good biography. I love a good biography when it’s a “standard” or “pure” biography that simply describes a person’s life from beginning to end. But I also love a good biography when it is written purposefully or thematically—when instead of chronologically detailing all the events of a person’s life it provides selective details and draws lessons for its readers. This is exactly the kind of biography Mary Mohler has written about Susannah Spurgeon in Susannah Spurgeon: Lessons for a Life of Joyful Eagerness in Christ. And it’s a joy to read. Susannah Spurgeon was, of course, the wife of the great preacher Charles Spurgeon, a man so uniquely gifted and whose influence was so vast, that everyone around him stood in his shadow. Yet while Susannah was in no way ashamed to be so closely identified with her husband that she is often only described in relation to him, she had a life, ministry, and impact that was all her own. Yes, she was Mrs. C.H. Spurgeon and plenty pleased with that fact. But she was also her own person with her own gifts, her own talents, her own means of serving others both alongside her husband and apart from him. Mohler writes this book with the particular audience of Christian women in mind. There is a sense in which it flows out of her ministry at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in which she serves as Director of the Seminary Wives Institute. “My goal,” she says, “is to write about what…]]>

I love a good biography. I love a good biography when it’s a “standard” or “pure” biography that simply describes a person’s life from beginning to end. But I also love a good biography when it is written purposefully or thematically—when instead of chronologically detailing all the events of a person’s life it provides selective details and draws lessons for its readers. This is exactly the kind of biography Mary Mohler has written about Susannah Spurgeon in Susannah Spurgeon: Lessons for a Life of Joyful Eagerness in Christ. And it’s a joy to read. Susannah Spurgeon was, of course, the wife of the great preacher Charles Spurgeon, a man so uniquely gifted and whose influence was so vast, that everyone around him stood in his shadow. Yet while Susannah was in no way ashamed to be so closely identified with her husband that she is often only described in relation to him, she had a life, ministry, and impact that was all her own. Yes, she was Mrs. C.H. Spurgeon and plenty pleased with that fact. But she was also her own person with her own gifts, her own talents, her own means of serving others both alongside her husband and apart from him. Mohler writes this book with the particular audience of Christian women in mind. There is a sense in which it flows out of her ministry at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in which she serves as Director of the Seminary Wives Institute. “My goal,” she says, “is to write about what…]]>

I love a good biography. I love a good biography when it’s a “standard” or “pure” biography that simply describes a person’s life from beginning to end. But I also love a good biography when it is written purposefully or thematically—when instead of chronologically detailing all the events of a person’s life it provides selective details and draws lessons for its readers. This is exactly the kind of biography Mary Mohler has written about Susannah Spurgeon in Susannah Spurgeon: Lessons for a Life of Joyful Eagerness in Christ. And it’s a joy to read.

Susannah Spurgeon was, of course, the wife of the great preacher Charles Spurgeon, a man so uniquely gifted and whose influence was so vast, that everyone around him stood in his shadow. Yet while Susannah was in no way ashamed to be so closely identified with her husband that she is often only described in relation to him, she had a life, ministry, and impact that was all her own. Yes, she was Mrs. C.H. Spurgeon and plenty pleased with that fact. But she was also her own person with her own gifts, her own talents, her own means of serving others both alongside her husband and apart from him.

Mohler writes this book with the particular audience of Christian women in mind. There is a sense in which it flows out of her ministry at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in which she serves as Director of the Seminary Wives Institute. “My goal,” she says, “is to write about what we as women—primarily women married to men in ministry, but also to Christian women in general—can learn from the remarkable life of Susannah Thompson Spurgeon.” And while she is neither a historian nor a biographer, “I have been a ministry wife for forty years and counting, and have been training future ministry wives for twenty-five years, so I have some stories to tell.”

And that introduces one of the strengths of this book. Because this is not a formal biography, she is able to make it personal and to integrate some of her own experiences—a factor that adds both human interest and life application. In fact, each chapter ends with a number of questions meant for quiet reflection.

Along the way, she chooses to focus on six themes, each of which is applicable to Christian women in general and to ministry wives in particular. She looks at Susannah’s life prior to being married and to her conversion to Christianity; she looks at her marriage and her devotion to her husband; she looks at her commitment to her home, both as a mother and as someone who carried out a ministry from the home; she looks at the deep physical suffering that for many years left her housebound and often bedridden; she looks at her response to some of the controversy she and her husband endured and also to her years as a widow. The book concludes with a selection of Susannah’s own writings for she was a talented and widely-read author in her own regard. In each case, Mohler quotes both original writings by Susannah and Charles Spurgeon along with information gleaned from their many biographers. And in each case, she ensures that the events of Susannah’s life lead naturally to application that is relevant to today’s readers.

Susannah Spurgeon: Lessons for a Life of Joyful Eagerness in Christ is an easy-to-read little biography that is as interesting as it is beautifully written. Whether for a ministry wife, for a Christian woman, or for anyone else (including men), I give it my highest recommendation.

]]> I wasn’t expecting to enjoy this book as much as I did. I enjoy reading a good biography as much as anyone, but was perhaps a bit skeptical about a book that, instead of focusing on an individual’s life and accomplishments, instead describes his spiritual and intellectual formation. Yet what could have been a mite dry was actually very compelling. It may be helpful context to state that I do not know Tim Keller personally and have neither met him nor corresponded with him. I also don’t think I’ve heard him preach more than once or twice. My exposure to him is really only through the three or four of his books that I have read. While I know a good number of people who consider him a major influence on their faith or ministry, I am not among them. I say all that because it means that I was reading about someone who is mostly a stranger, though one I’ve sometimes admired from afar and sometimes had concerns about. Collin Hansen knows Keller well and came to know him far better in preparing this book. He shares the book’s purpose in the opening pages. Unlike a traditional biography, this book tells Keller’s story from the perspective of his influences, more than his influence. Spend any time around Keller and you’ll learn that he doesn’t enjoy talking about himself. But he does enjoy talking—about what he’s reading, what he’s learning, what he’s seeing. The story of Tim Keller is the story of his spiritual and…]]>

I wasn’t expecting to enjoy this book as much as I did. I enjoy reading a good biography as much as anyone, but was perhaps a bit skeptical about a book that, instead of focusing on an individual’s life and accomplishments, instead describes his spiritual and intellectual formation. Yet what could have been a mite dry was actually very compelling. It may be helpful context to state that I do not know Tim Keller personally and have neither met him nor corresponded with him. I also don’t think I’ve heard him preach more than once or twice. My exposure to him is really only through the three or four of his books that I have read. While I know a good number of people who consider him a major influence on their faith or ministry, I am not among them. I say all that because it means that I was reading about someone who is mostly a stranger, though one I’ve sometimes admired from afar and sometimes had concerns about. Collin Hansen knows Keller well and came to know him far better in preparing this book. He shares the book’s purpose in the opening pages. Unlike a traditional biography, this book tells Keller’s story from the perspective of his influences, more than his influence. Spend any time around Keller and you’ll learn that he doesn’t enjoy talking about himself. But he does enjoy talking—about what he’s reading, what he’s learning, what he’s seeing. The story of Tim Keller is the story of his spiritual and…]]>

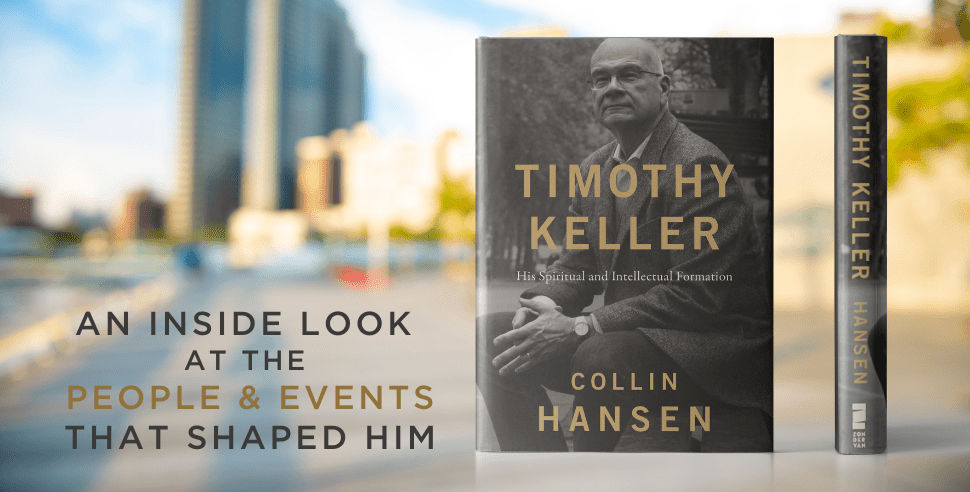

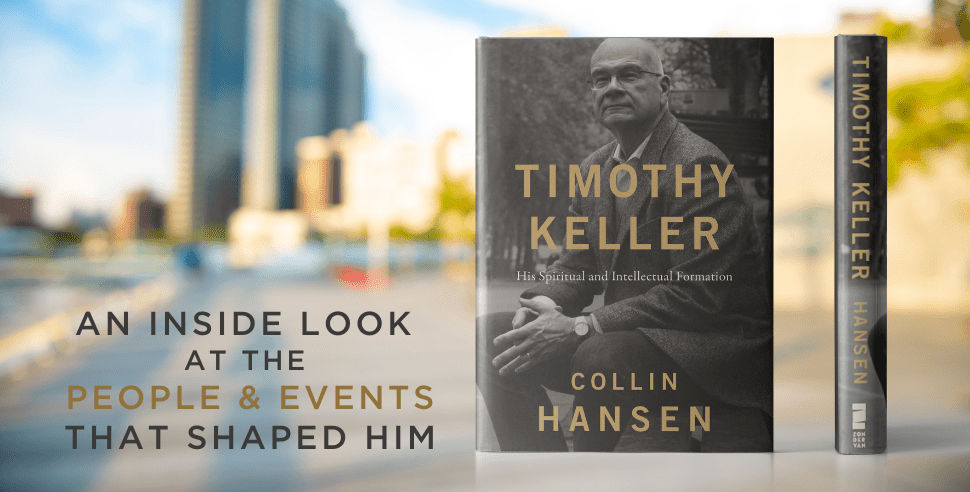

I wasn’t expecting to enjoy this book as much as I did. I enjoy reading a good biography as much as anyone, but was perhaps a bit skeptical about a book that, instead of focusing on an individual’s life and accomplishments, instead describes his spiritual and intellectual formation. Yet what could have been a mite dry was actually very compelling.

It may be helpful context to state that I do not know Tim Keller personally and have neither met him nor corresponded with him. I also don’t think I’ve heard him preach more than once or twice. My exposure to him is really only through the three or four of his books that I have read. While I know a good number of people who consider him a major influence on their faith or ministry, I am not among them. I say all that because it means that I was reading about someone who is mostly a stranger, though one I’ve sometimes admired from afar and sometimes had concerns about.

Collin Hansen knows Keller well and came to know him far better in preparing this book. He shares the book’s purpose in the opening pages.

Unlike a traditional biography, this book tells Keller’s story from the perspective of his influences, more than his influence. Spend any time around Keller and you’ll learn that he doesn’t enjoy talking about himself. But he does enjoy talking—about what he’s reading, what he’s learning, what he’s seeing.

The story of Tim Keller is the story of his spiritual and intellectual influences—from the woman who taught him how to read the Bible, to the professor who taught him to preach Jesus from every text, to the sociologist who taught him to see beneath society’s surface. … This is the story of the people, the books, the lectures, and ultimately the God who formed Timothy James Keller.

And so it begins with his childhood and a father who was quite withdrawn and a mother who, though she loved her children, was extremely controlling. She led her family to an Evangelical Congregational church which “emphasized human effort in maintaining salvation and achieving sinless perfection. Both at home and in church, Tim Keller learned this second form of legalism—that of the fundamentalist variety. By the time Tim was leaving home to attend college, he didn’t just know about Martin Luther; he could personally relate to Luther, who had been afflicted with a pathologically overscrupulous conscience that expected perfection from himself in seeking to live up to his standards and potential.”

Keller enrolled as a religion major in Bucknell University where he fell under the influence of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and soon professed faith in Christ. His connection with InterVarsity would develop within him a zeal for evangelism and a method for reading and understanding Scripture. In this timeframe he would also be exposed to the ministries of John Stott, Elisabeth Elliot, Martyn Lloyd-Jones and others, all of whom would shape him in different ways. Even more importantly, he would come to know Kathy Kristy who would not only become his wife, but also his most formative intellectual and spiritual influence, for when “you’re writing about Tim Keller, you’re really writing about Tim and Kathy, a marriage between intellectual equals who met in seminary over shared commitment to ministry and love for literature, along with serious devotion to theology.”

The book goes on to tell of the influence of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, of R.C. Sproul and his Ligonier Valley Study Center, and of Francis Schaeffer and L’Abri. It tells of Keller’s time at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and the professors there, and his discovery of the writings of Jonathan Edwards. Then it advances to his first pastorate in Hopewell, Virginia and to his time as a professor at Westminster Theological Seminary, pausing to tell, at length, of the impact of Edmund Clowney. And, then, finally it comes New York City, Redeemer Church, Redeemer City-to-City, and Keller’s many books, along with the people living and dead who played essential roles in helping him develop his strategy for reaching cities for Christ.

Throughout the book, Hansen shows Keller as a man whose foremost gifting is not as an original thinker but as an analyzer and synthesizer who reads deeply and widely, pulling together insights from a host of others. “Having one hero would be derivative; having one hundred heroes means you’ve drunk deeply by scouring the world for the purest wells. This God-given ability to integrate disparate sources and then share insights with others has been observed by just about anyone who has known Keller, going back to his college days. He’s the guide to the gurus. You get their best conclusions, with Keller’s unique twist.” And hence the great conclusion at the end of it all is that if you appreciate Tim Keller the best thing you can do is focus less on him and more on the people who taught and influenced him.

After I finished the book I surveyed its endorsements and thought Sinclair Ferguson’s was especially on-point: “Here is the story of a man possessed of unusual native gifts of analysis and synthesis, of the home and family life that has shaped him, of people both long dead and contemporary whose insights he has taken hold of in the interests of communicating the gospel, and also of the twists and turns of God’s providence in his life. These pages may well have been titled Becoming Tim Keller. That ‘becoming’ has been neither a quick nor an easy road. But Collin Hansen’s account of it will be as challenging to readers as it is instructive.”

Ferguson says it just right. Whether you have been influenced by Keller or not, whether you admire him or not, I believe you will enjoy this account of his life framed around his intellectual and spiritual development. Told through the pen of an especially talented a writer, it is a fascinating and compelling narrative. It may just get you thinking about who has formed you and compel you to praise God for the people, the preachers, the books, and the organizations that have made you who you are.

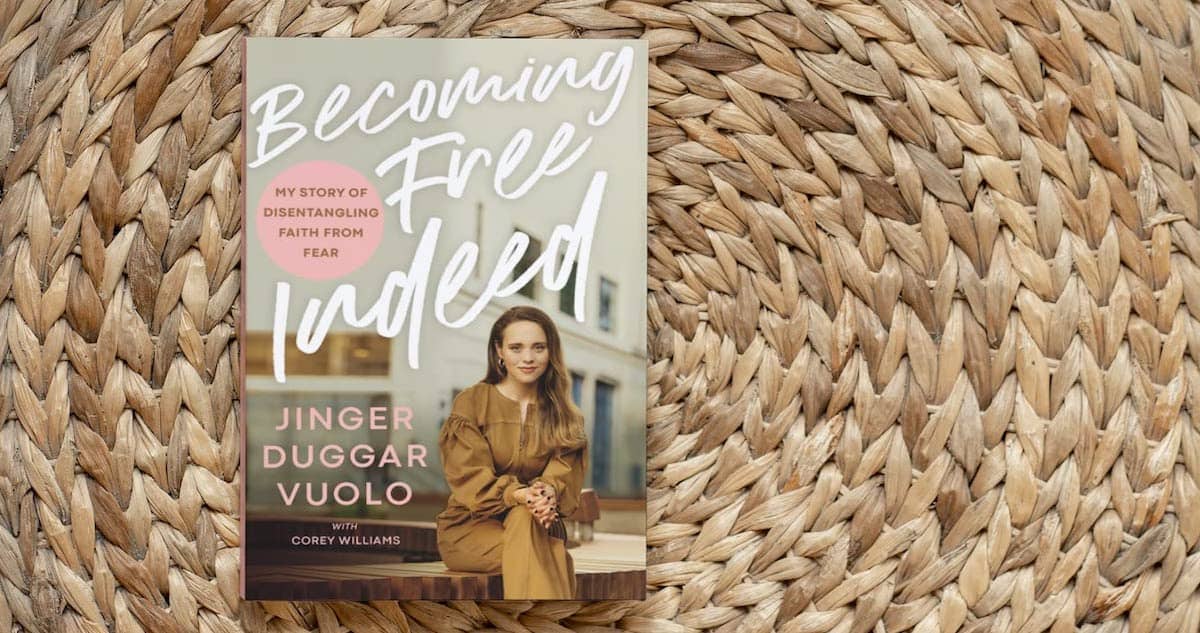

]]> I suppose I should probably preface what follows by saying that I have never watched as much as a moment of any show by or about the Duggar family. I once had a very cordial chat with Jinger Vuolo (formerly Duggar) at a conference without knowing she was a reality TV personality and probably the best-known person at the whole event. Such is my knowledge of television! And so when I chose to buy and read her new memoir Becoming Free Indeed it was not because I am a fan of her family or heavily invested in her story, but because from the bit I had heard of it, it would powerfully contrast some other recent memoirs. I’ll explain that as I go. But first, for those who are as ignorant as I am, Jinger Vuolo is one of the 19 children born to Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar. For many years the lives of the Duggar family were broadcast on the TLC shows 19 Kids and Counting and Counting On. This put Jinger and her family squarely in the public eye and gave them a forum to showcase their Christian faith and values. Yet these values were closely tied to the troubling ministry of Bill Gothard. For many years Gothard had a near cult-like following and exercised tremendous power over many of those who relied on his interpretation of the Bible—including the Duggars. Yet what he taught was only ever loosely drawn from Scripture and always extremely legalistic. As suggested by the book’s subtitle,…]]>

I suppose I should probably preface what follows by saying that I have never watched as much as a moment of any show by or about the Duggar family. I once had a very cordial chat with Jinger Vuolo (formerly Duggar) at a conference without knowing she was a reality TV personality and probably the best-known person at the whole event. Such is my knowledge of television! And so when I chose to buy and read her new memoir Becoming Free Indeed it was not because I am a fan of her family or heavily invested in her story, but because from the bit I had heard of it, it would powerfully contrast some other recent memoirs. I’ll explain that as I go. But first, for those who are as ignorant as I am, Jinger Vuolo is one of the 19 children born to Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar. For many years the lives of the Duggar family were broadcast on the TLC shows 19 Kids and Counting and Counting On. This put Jinger and her family squarely in the public eye and gave them a forum to showcase their Christian faith and values. Yet these values were closely tied to the troubling ministry of Bill Gothard. For many years Gothard had a near cult-like following and exercised tremendous power over many of those who relied on his interpretation of the Bible—including the Duggars. Yet what he taught was only ever loosely drawn from Scripture and always extremely legalistic. As suggested by the book’s subtitle,…]]>

I suppose I should probably preface what follows by saying that I have never watched as much as a moment of any show by or about the Duggar family. I once had a very cordial chat with Jinger Vuolo (formerly Duggar) at a conference without knowing she was a reality TV personality and probably the best-known person at the whole event. Such is my knowledge of television! And so when I chose to buy and read her new memoir Becoming Free Indeed it was not because I am a fan of her family or heavily invested in her story, but because from the bit I had heard of it, it would powerfully contrast some other recent memoirs. I’ll explain that as I go.

But first, for those who are as ignorant as I am, Jinger Vuolo is one of the 19 children born to Jim Bob and Michelle Duggar. For many years the lives of the Duggar family were broadcast on the TLC shows 19 Kids and Counting and Counting On. This put Jinger and her family squarely in the public eye and gave them a forum to showcase their Christian faith and values. Yet these values were closely tied to the troubling ministry of Bill Gothard.

For many years Gothard had a near cult-like following and exercised tremendous power over many of those who relied on his interpretation of the Bible—including the Duggars. Yet what he taught was only ever loosely drawn from Scripture and always extremely legalistic. As suggested by the book’s subtitle, he kept people in a state of spiritual fear and uncertainty. His ministry exploded a few years ago when a whole series of women credibly accused him of sexual harassment and assault.

Vuolo’s book is essentially the story of her coming to terms with the form of Christianity she experienced in her childhood and her growing awareness of its many shortcomings. But it is also her account of discovering a form of Christianity that is much more consistent with the Bible and much more satisfying. And what I described in the last sentence is precisely why I read her memoir.

We can turn to any number of books to find stories of people who were raised in Christian contexts that were either marked by theological error or moral scandal. Many of these books tell of the author ultimately abandoning her faith. Such tales of deconstruction are all the rage and often sell in vast quantities. And a good number of them are written by people who were raised in contexts much more innocuous than Gothardism. It wouldn’t have been shocking if Vuolo’s memoir had been of that kind.

But thankfully it is not. Rather than describing someone abandoning her faith, Becoming Free Indeed describes someone persistently searching the Scriptures to refine her faith. Rather than describing someone walking away from God, it describes someone drawing closer to him. It provides a powerful contrast to those who chose to revoke their faith by telling of someone who chose to not only remain a Christian, but to grow in her confidence in the Lord and to follow him with even greater passion and commitment.

It tells all of this in the form of a memoir that is interesting on a human-interest level and encouraging on a spiritual level. It tells all of this while protecting confidentiality and respecting parents and family. It tells all of this in a book that I rather enjoyed and gladly commend.

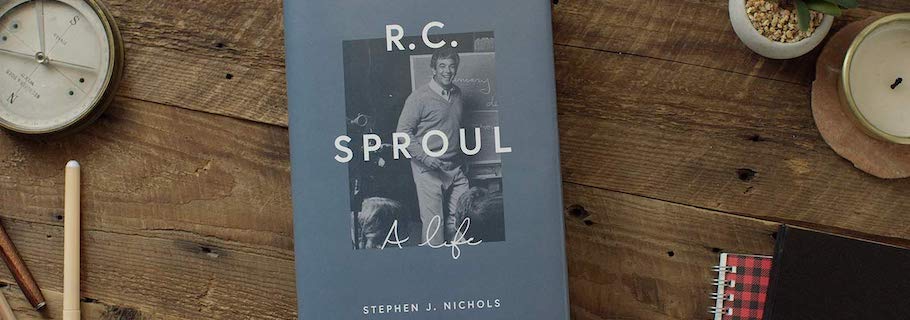

]]> I used to say that no living theologian had impacted my faith more than R.C. Sproul. His books changed me, formed me, strengthened me. His sermons and conference talks never failed to grip my heart and thrill my soul. His teaching series fed my mind and taught me how to live out my faith. In so many ways he guided me into Christian infancy and toward Christian maturity. I was one of many believers around the world who grieved his death as a personal tragedy, a significant loss. Though he is no longer a living theologian, I often still recount how much I owe to him. I often still thank God for him. It was inevitable that Sproul would be the subject of biographies and appropriate that Stephen Nichols should write the first. After all, Nichols served alongside Sproul for many years at both Ligonier Ministries and Reformation Bible College. He knew Sproul in many settings both personal and professional. He sat beside him in corporate board rooms and across from him in restaurant dining rooms. He chatted with him casually and interviewed him formally. Through it all he gained a deep understanding and deep appreciation of his subject. And it shows in the warm pages of this tremendous book. R.C. Sproul: A Life falls within the best tradition of Christian biography which is for friends to be the first to commemorate the life of someone they knew and loved. Nichols tells of Sproul’s beginnings in Pittsburgh, of the positive influence of his parents and…]]>

I used to say that no living theologian had impacted my faith more than R.C. Sproul. His books changed me, formed me, strengthened me. His sermons and conference talks never failed to grip my heart and thrill my soul. His teaching series fed my mind and taught me how to live out my faith. In so many ways he guided me into Christian infancy and toward Christian maturity. I was one of many believers around the world who grieved his death as a personal tragedy, a significant loss. Though he is no longer a living theologian, I often still recount how much I owe to him. I often still thank God for him. It was inevitable that Sproul would be the subject of biographies and appropriate that Stephen Nichols should write the first. After all, Nichols served alongside Sproul for many years at both Ligonier Ministries and Reformation Bible College. He knew Sproul in many settings both personal and professional. He sat beside him in corporate board rooms and across from him in restaurant dining rooms. He chatted with him casually and interviewed him formally. Through it all he gained a deep understanding and deep appreciation of his subject. And it shows in the warm pages of this tremendous book. R.C. Sproul: A Life falls within the best tradition of Christian biography which is for friends to be the first to commemorate the life of someone they knew and loved. Nichols tells of Sproul’s beginnings in Pittsburgh, of the positive influence of his parents and…]]>

I used to say that no living theologian had impacted my faith more than R.C. Sproul. His books changed me, formed me, strengthened me. His sermons and conference talks never failed to grip my heart and thrill my soul. His teaching series fed my mind and taught me how to live out my faith. In so many ways he guided me into Christian infancy and toward Christian maturity. I was one of many believers around the world who grieved his death as a personal tragedy, a significant loss. Though he is no longer a living theologian, I often still recount how much I owe to him. I often still thank God for him.

It was inevitable that Sproul would be the subject of biographies and appropriate that Stephen Nichols should write the first. After all, Nichols served alongside Sproul for many years at both Ligonier Ministries and Reformation Bible College. He knew Sproul in many settings both personal and professional. He sat beside him in corporate board rooms and across from him in restaurant dining rooms. He chatted with him casually and interviewed him formally. Through it all he gained a deep understanding and deep appreciation of his subject. And it shows in the warm pages of this tremendous book.

R.C. Sproul: A Life falls within the best tradition of Christian biography which is for friends to be the first to commemorate the life of someone they knew and loved. Nichols tells of Sproul’s beginnings in Pittsburgh, of the positive influence of his parents and the negative influence of liberal theologians, of meeting and marrying Vesta, of coming to faith in Jesus, of finding his great passion for the word of God. He tells of the founding of the L’Abri-like Ligonier Valley Study Center, of Sproul’s growing influence across the evangelical church, and his dawning awareness that he could best deploy his talents as a teacher as much as a preacher. He focuses on the battle for biblical inerrancy, on the place of classical apologetics, of the themes of divine holiness and sovereignty, and on the great desire to protect the gospel from the confusion of ecumenism.

Through it all, Nichols paints a portrait of a man who was transformed by the Bible and gripped by God’s character—a man who knew God and who longed to make him known. He shows him to be a man of kindness and integrity, of joy and generosity, of seriousness and silliness. He shows him to be a man who adored his wife, loved his family, and honored his friends. He shows him to be a man God raised up to be a gentle warrior, a man with a warm heart and resolute spirit, a man who would love a sinner but not suffer a fool. In other words, he shows him to be exactly the man in private that he appeared to be in public.

R.C. Sproul: A Life is one of the few biographies I’ve read that recounts the life of a person I actually met and actually spoke to (though not nearly as much as I would have liked). Even better, it’s one of the few that recounts the life of a person who made a deep and immediate impact on my own. Though eternity alone will unravel all I owe to R.C. Sproul, this biography helps me understand just a little bit better. It causes me to thank God for the life, ministry, and testimony of so faithful a servant.

]]> In recent weeks I’ve encountered a number of people who have never read a biography. While there’s no law commanding the reading of biographies, there are certainly many good reasons to make them a regular part of a reading diet. Today I want to offer just a few suggestions and recommendations for people who are approaching biography for the first time, or for the first time in a long while. Three Tips I’ll begin with a few suggestions for getting started in biography. First, I’d recommend beginning with a biography that is relatively short. While William Manchester’s three-volume set on Winston Churchill is brilliant, it is also more than a little daunting (the audiobook is 131 hours long!). You’re probably better-off beginning with something more manageable. Second, I’d recommend beginning with a biography that is generally positive in its tone. While there’s value in reading about false teachers or even tricky figures—those who may have been brilliantly sold-out for the Lord in one way but living in open defiance in another—it can introduce a level of complexity to properly interpreting a life. Before reading about heretics, charlatans, and the ones who aren’t so easily categorized, it may be helpful to get a good baseline of godly characters. Third, start with a well-known figure. Though it’s not always the case, it’s generally true that history mostly remembers the best and the worst figures of any period. There are a few people in every generation who tower over their peers and they represent a great place to…]]>

In recent weeks I’ve encountered a number of people who have never read a biography. While there’s no law commanding the reading of biographies, there are certainly many good reasons to make them a regular part of a reading diet. Today I want to offer just a few suggestions and recommendations for people who are approaching biography for the first time, or for the first time in a long while. Three Tips I’ll begin with a few suggestions for getting started in biography. First, I’d recommend beginning with a biography that is relatively short. While William Manchester’s three-volume set on Winston Churchill is brilliant, it is also more than a little daunting (the audiobook is 131 hours long!). You’re probably better-off beginning with something more manageable. Second, I’d recommend beginning with a biography that is generally positive in its tone. While there’s value in reading about false teachers or even tricky figures—those who may have been brilliantly sold-out for the Lord in one way but living in open defiance in another—it can introduce a level of complexity to properly interpreting a life. Before reading about heretics, charlatans, and the ones who aren’t so easily categorized, it may be helpful to get a good baseline of godly characters. Third, start with a well-known figure. Though it’s not always the case, it’s generally true that history mostly remembers the best and the worst figures of any period. There are a few people in every generation who tower over their peers and they represent a great place to…]]>

In recent weeks I’ve encountered a number of people who have never read a biography. While there’s no law commanding the reading of biographies, there are certainly many good reasons to make them a regular part of a reading diet. Today I want to offer just a few suggestions and recommendations for people who are approaching biography for the first time, or for the first time in a long while.

Three Tips

I’ll begin with a few suggestions for getting started in biography.

First, I’d recommend beginning with a biography that is relatively short. While William Manchester’s three-volume set on Winston Churchill is brilliant, it is also more than a little daunting (the audiobook is 131 hours long!). You’re probably better-off beginning with something more manageable.

Second, I’d recommend beginning with a biography that is generally positive in its tone. While there’s value in reading about false teachers or even tricky figures—those who may have been brilliantly sold-out for the Lord in one way but living in open defiance in another—it can introduce a level of complexity to properly interpreting a life. Before reading about heretics, charlatans, and the ones who aren’t so easily categorized, it may be helpful to get a good baseline of godly characters.

Third, start with a well-known figure. Though it’s not always the case, it’s generally true that history mostly remembers the best and the worst figures of any period. There are a few people in every generation who tower over their peers and they represent a great place to begin.

Ten Recommendations

Here are ten biography recommendations for people who are just getting started. I’ll try to keep them focused on Christians and keep them shorter than 300 pages. Before I do that, let me recommend a few series. Christian Focus’s History Makers are biographies of key figures that tend to be around the 200-page mark. I’ve read quite a few of them and they have all been excellent. Steve Lawson’s A Long Line of Godly Men series is meant to serve as introductions to notable figures, both in their lives and impact, so they tend to include a relatively short overview of the subject’s life followed by topical discussions of his accomplishments. John Piper’s The Swans Are Not Silent series contain several short biographies per volume.

And now, the biographies:

- Amy Carmichael: Beauty For Ashes by Iain Murray. Carmichael was a missionary to India who receives a short but solid treatment from Iain Murray. I love the respect he has for her, even though she represents quite a different theological tradition.

- Spurgeon: A Biography by Arnold Dallimore. This biography is almost too short to tell such a life, but it serves as a great introduction to Charles Spurgeon, the Prince of Preachers. (Next steps: Living by Revealed Truth by Tom Nettles or Spurgeon’s autobiography.)

- Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery by Eric Metaxas. Traces the life of the British politician who dedicated his life to revoking slavery. (If you enjoy this one, please upgrade to William Hague’s William Wilberforce which, though quite a bit longer, is quite a bit better.)

- John & Betty Stam: Missionary Martyrs by Vance Christie. The Stams were missionaries martyred in China in the 1930s. Their deaths sparked a great resurgence of missionary fervor.

- John Calvin: Pilgrim and Pastor by Robert Godfrey. You won’t do better than this as a short introduction to John Calvin. And whether you’re for or against Calvinism, you can’t deny the impact of Calvin in the making of the modern world, so he’s a figure worth knowing. (Next step: Calvin by Bruce Gordon)

- George Whitefield: God’s Anointed Servant in the Great Revival of the Eighteenth Century by Arnold Dallimore. This is a condensed version of Dallimore’s two-volume set. (Next steps: George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father by Thomas Kidd.)

- A Short Life of Jonathan Edwards by George Marsden. This is a short biography that pairs well with Marsden’s larger account of Edwards’ life.

- John MacArthur: Servant of the Word and Flock by Iain Murray. There aren’t too many biographies available for subjects who are still living, but this one is an exception. Murray actually set out to write just a small work, but kept going until it became full-length.

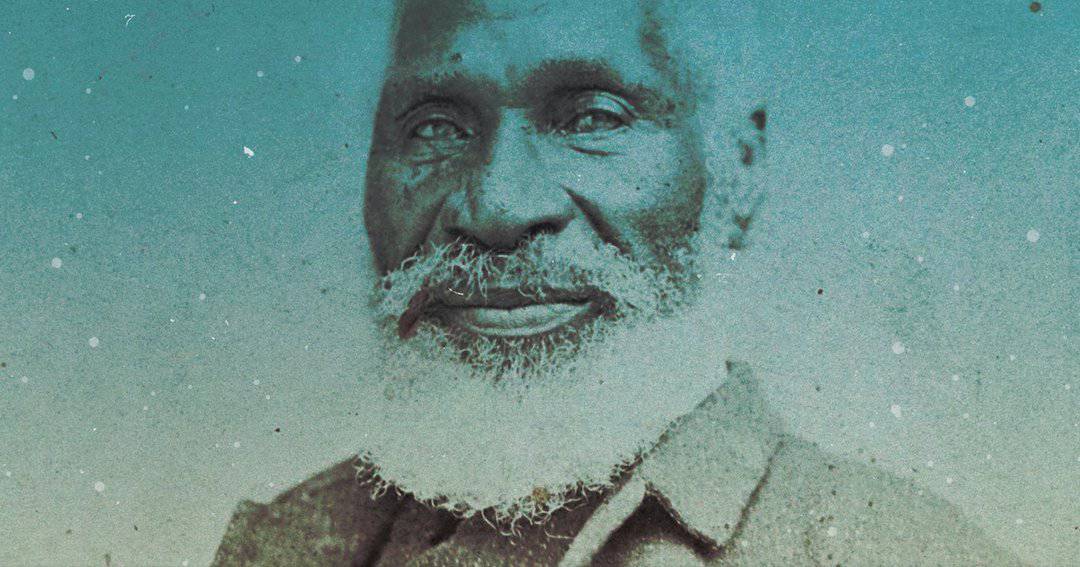

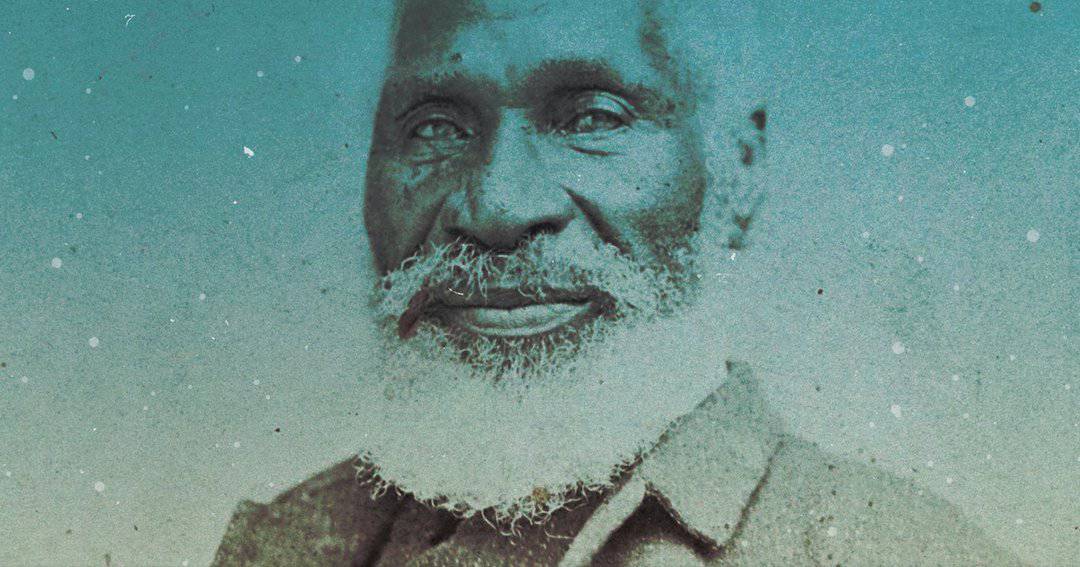

- The Road to Dawn: Josiah Henson and the Story That Sparked the Civil War by Jared Brock. Josiah Henson should probably be better known (since he was the inspiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom”). This biography introduces his life and impact.

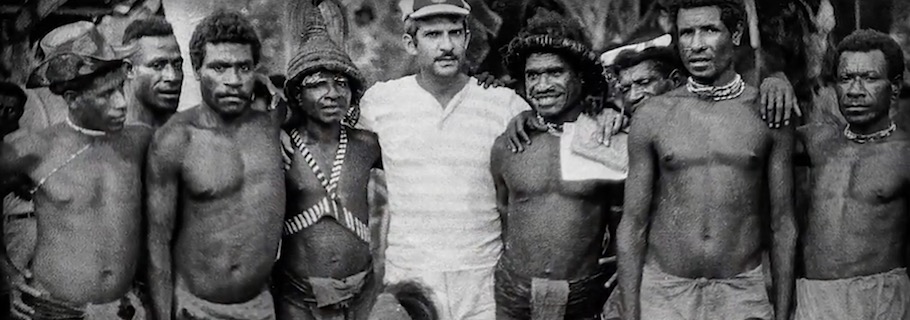

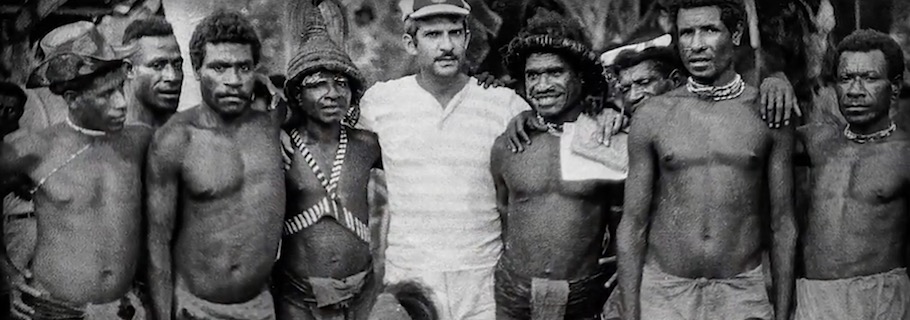

- John G. Paton: Missionary to the Cannibals of the South Seas by Paul Schlehlein. Paton is a courageous figure who deserves to be known, and this biography does a great job of introducing him.

I promised ten, so will stop there. And even if none of these look particularly appealing, do consider picking up a different biography and giving it a read. I suspect you’ll be glad you did.

]]> As I’ve traveled the world over the past year, I’ve made many new friends. Some of these friends are living, but many more of them have long since gone to glory, and I’ve had to meet them through their biographies and through the objects they’ve left behind. One of my new friends is Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. In what follows, I want to briefly introduce you to her. She was born into prominence. She was born on August 24, 1707 in the forty-room Astwell Manor House, a member of one of the oldest of England’s Aristocratic families, the Shirleys. Though the family was fantastically wealthy, it was also terribly unhappy, and Selina’s mother left her father when Selina was only six years old. She was left in the care of her father and soon showed herself a serious-minded child who often thought about the state of her soul. She married into even greater prominence. Selina married Theophilus Hastings, the Ninth Earl of Huntingdon, on June 3, 1728, when she was 21 and he was 32. She was welcomed into the Hastings family by Theophilus’s sisters with whom she became close friends. Together they moved in the most elite circles and spent time with some of the most important figures of the time. Though her marriage to Theophilus was marked by great love and affection, it was also marked by illness and loss. Together they had seven children, only one of whom outlived her. She got saved in 1739. Though Selina was always a moral…]]>

As I’ve traveled the world over the past year, I’ve made many new friends. Some of these friends are living, but many more of them have long since gone to glory, and I’ve had to meet them through their biographies and through the objects they’ve left behind. One of my new friends is Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. In what follows, I want to briefly introduce you to her. She was born into prominence. She was born on August 24, 1707 in the forty-room Astwell Manor House, a member of one of the oldest of England’s Aristocratic families, the Shirleys. Though the family was fantastically wealthy, it was also terribly unhappy, and Selina’s mother left her father when Selina was only six years old. She was left in the care of her father and soon showed herself a serious-minded child who often thought about the state of her soul. She married into even greater prominence. Selina married Theophilus Hastings, the Ninth Earl of Huntingdon, on June 3, 1728, when she was 21 and he was 32. She was welcomed into the Hastings family by Theophilus’s sisters with whom she became close friends. Together they moved in the most elite circles and spent time with some of the most important figures of the time. Though her marriage to Theophilus was marked by great love and affection, it was also marked by illness and loss. Together they had seven children, only one of whom outlived her. She got saved in 1739. Though Selina was always a moral…]]>

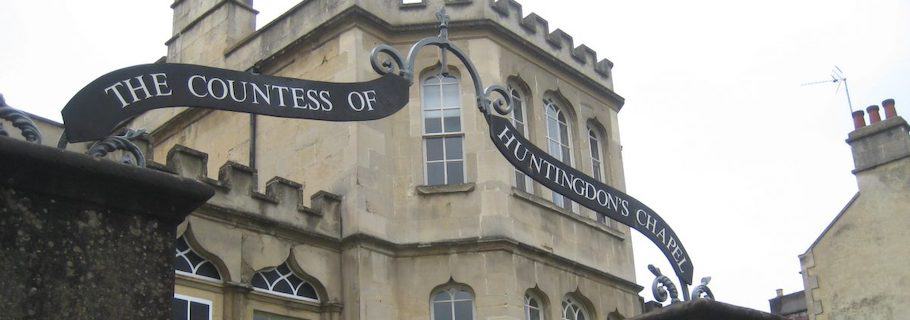

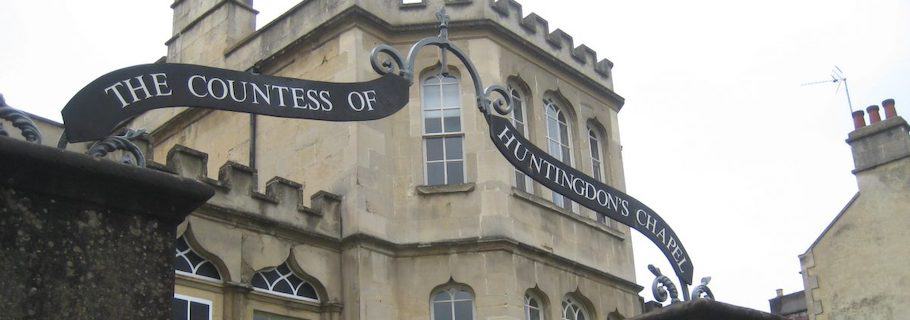

As I’ve traveled the world over the past year, I’ve made many new friends. Some of these friends are living, but many more of them have long since gone to glory, and I’ve had to meet them through their biographies and through the objects they’ve left behind. One of my new friends is Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. In what follows, I want to briefly introduce you to her.

She was born into prominence. She was born on August 24, 1707 in the forty-room Astwell Manor House, a member of one of the oldest of England’s Aristocratic families, the Shirleys. Though the family was fantastically wealthy, it was also terribly unhappy, and Selina’s mother left her father when Selina was only six years old. She was left in the care of her father and soon showed herself a serious-minded child who often thought about the state of her soul.

She married into even greater prominence. Selina married Theophilus Hastings, the Ninth Earl of Huntingdon, on June 3, 1728, when she was 21 and he was 32. She was welcomed into the Hastings family by Theophilus’s sisters with whom she became close friends. Together they moved in the most elite circles and spent time with some of the most important figures of the time. Though her marriage to Theophilus was marked by great love and affection, it was also marked by illness and loss. Together they had seven children, only one of whom outlived her.

She got saved in 1739. Though Selina was always a moral and upright person, it was only in her early thirties that she began to realize that she was counting on her good deeds to earn merit with God. Under the preaching of the early Methodists, she came to faith in Jesus Christ sometime in mid-1739. Theophilus probably did as well, but the historical record is less certain for him. Though she remained in the Church of England, she was always associated with Methodists, something that damaged her reputation among her peers. She developed close friendships with John and Charles Wesley and with George Whitefield. She was especially close to Charles and his wife Sally, whom she loved almost as a daughter.

She reached out to her aristocratic peers. Soon after her conversion she became convinced that she should reach out to her peers with the gospel. Because of her association with Methodists, she did this at great cost to her reputation. One of them rebuked her, saying, “It is monstrous to be told that you have a heart as sinful as the common wretches that crawl on the earth. This is highly offensive and insulting; and I cannot but wonder that your Ladyship should relish any sentiments so much at variance with high rank and good breeding.” But she continued to share the gospel with nobility, monarchy, and commoners alike.

She took sides with George Whitefield. John Wesley eventually broke ranks with George Whitefield over issues related to Calvinism. Selina attempted to mediate this dispute, but was unsuccessful. Though she was initially persuaded by Wesley, through her own studies she came to prefer the Calvinistic interpretation of Scripture. She eventually hired Whitefield as her personal chaplain so he would preach on her estate. This allowed her to invite her aristocratic peers to hear the great gospel preacher of the age, and many came to saving faith.

She became one of the great philanthropists of her time. Blessed with great wealth, she determined to use what she had for God’s glory.

She was committed to training preachers. Having been saved by evangelical preaching, she was committed to training more preachers who would boldly proclaim the Word of God. For this reason she founded a seminary in Trevecca, Wales, under the leadership of Howell Harris. The initial students were men who had been expelled from Oxford for their Methodist leanings. The school opened in 1768 with Whitefield preaching to mark the occasion. (When she experienced trouble finding a Latin and Greek teacher, she soon hired a twelve-year-old prodigy to serve as a tutor!)

She was committed to biblical gender roles. Selina was committed to what today we might call “complementarian” principles related to gender roles, so she never preached or instructed preachers. Yet she certainly did encourage them, as proven by this letter from William Grimshaw: “What blessing did the Lord shower upon us the last time you were here! And how did our hearts burn within us to proclaim his love and grace to perishing sinners! Come and animate us afresh—aid us by your counsels and your prayers—communicate a spark of your glowing zeal, and stir us up to renewed activity in the cause of God.” Also, because she paid the salaries of a great number of preachers, she felt liberty to maintain an employer-employee relationship with many of them.

She was committed to financing local churches. Through her life she was involved in purchasing, renovating, and building local churches where evangelicals could preach. By the end of her life, she had 116 churches as part of her “Connexion” network, with more than 60 of them built or financed with her help. Though few of these survive today, a wonderful example is the chapel she built at Bath. Though it is now the Museum of Bath Architecture, much of the interior remains as it was, including the high pulpit where Whitefield preached the inaugural sermon. The museum has a small exhibit dedicated to her that includes a couple of items of particular interest.

She was a dedicated to praying and corresponding. Selina set aside significant time each day to read the Bible and pray for herself and others. She would also spend hours each day writing letters to her friends, family members, acquaintances, students, and preachers. These would often contain encouragements or theological teaching and reflection. Through her commitment to learning, she became a strong theologian.

She willingly deprived herself to support Christian ministry. All throughout her life, she gave with extreme generosity. She eventually went so far as to have her property plowed and planted with corn so she could earn an income from it. By the time she died, she had given away the vast majority of her wealth. A friend observed, “I believe she often possessed no more than the gown she wore.” She deprived herself of a lot of luxuries in order to carry out her work of philanthropy.

She died on June 17, 1791. She was 83 when she died and, according to her wishes, was buried with great simplicity. There was no great monument, no fancy coffin, and no crowd of mourners. Rather, she was buried in simplicity beside her husband with only three people in attendance.

Following her death, a friend remembered her in this way: “Thousands, I may say tens of thousands, in various parts of the kingdom heard the gospel through her instrumentality that in all probability would never have heard it at all; and I believe through eternity will have cause to bless God that she ever existed. She was truly and emphatically a Mother in Israel, and though she was far from a perfect character, yet I hesitate not to say that among the illustrious and noble of the country she has not left her equal.” But perhaps it was King George III who said it best: “I wish there was a Lady Huntingdon in every diocese in my kingdom.” May the Lord raise up many more like her!

There have been a number of biographies written about Selina Hastings. My top recommendation, and the only one still in print and widely available, is Selina Countess of Huntingdon by Faith Cook. It’s from her book that most of my information was drawn.

]]> History is packed full of fascinating figures. Some of these are men and women who were raised to lay claim to great positions—Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Queen Elizabeth II. Some of these are men and women who come from nowhere and nothing but still rose to great prominence. Among these we find Aimee Semple McPherson, the preacher and evangelist who may well have reigned as America’s best-known woman for much of her life. Here are a few key facts about her. She was Canadian before she was American. She was born as Aimee Kennedy in Salford, Ontario, Canada on October 9, 1890, to James and Minnie. Her parents were fully 35 years apart in age with James being 50 and Minnie 15 when they married. Minnie was enthusiastically committed to the Salvation Army and longed to go into full-time missionary service. Unable to do so because of her family obligations, she dedicated her unborn first child to ministry, convinced she would give birth to a daughter. She promised God she would give this girl “unreservedly into your service, that she may preach the word I should have preached, fill the place I should have filled, and live the life I should have lived in Thy service.” Her first child was, indeed, a girl, whom she named Aimee. She professed faith in 1907. Aimee had a conversion experience under the preaching of Robert Semple. Semple had been born in Ireland, then migrated to the United States where he encountered some of the earliest Pentecostals. He…]]>

History is packed full of fascinating figures. Some of these are men and women who were raised to lay claim to great positions—Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Queen Elizabeth II. Some of these are men and women who come from nowhere and nothing but still rose to great prominence. Among these we find Aimee Semple McPherson, the preacher and evangelist who may well have reigned as America’s best-known woman for much of her life. Here are a few key facts about her. She was Canadian before she was American. She was born as Aimee Kennedy in Salford, Ontario, Canada on October 9, 1890, to James and Minnie. Her parents were fully 35 years apart in age with James being 50 and Minnie 15 when they married. Minnie was enthusiastically committed to the Salvation Army and longed to go into full-time missionary service. Unable to do so because of her family obligations, she dedicated her unborn first child to ministry, convinced she would give birth to a daughter. She promised God she would give this girl “unreservedly into your service, that she may preach the word I should have preached, fill the place I should have filled, and live the life I should have lived in Thy service.” Her first child was, indeed, a girl, whom she named Aimee. She professed faith in 1907. Aimee had a conversion experience under the preaching of Robert Semple. Semple had been born in Ireland, then migrated to the United States where he encountered some of the earliest Pentecostals. He…]]>

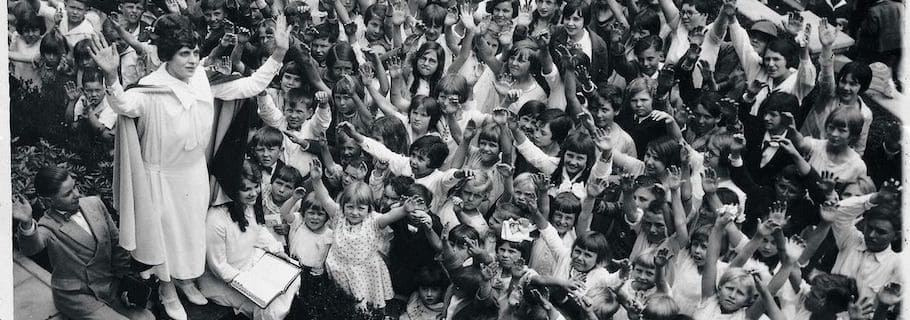

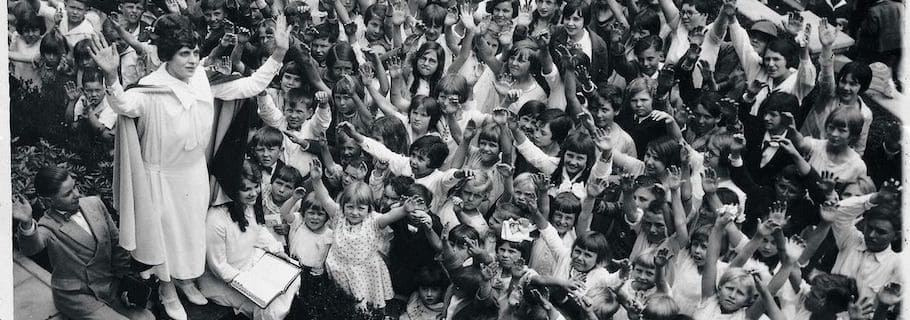

History is packed full of fascinating figures. Some of these are men and women who were raised to lay claim to great positions—Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Queen Elizabeth II. Some of these are men and women who come from nowhere and nothing but still rose to great prominence. Among these we find Aimee Semple McPherson, the preacher and evangelist who may well have reigned as America’s best-known woman for much of her life. Here are a few key facts about her.

She was Canadian before she was American. She was born as Aimee Kennedy in Salford, Ontario, Canada on October 9, 1890, to James and Minnie. Her parents were fully 35 years apart in age with James being 50 and Minnie 15 when they married. Minnie was enthusiastically committed to the Salvation Army and longed to go into full-time missionary service. Unable to do so because of her family obligations, she dedicated her unborn first child to ministry, convinced she would give birth to a daughter. She promised God she would give this girl “unreservedly into your service, that she may preach the word I should have preached, fill the place I should have filled, and live the life I should have lived in Thy service.” Her first child was, indeed, a girl, whom she named Aimee.

She professed faith in 1907. Aimee had a conversion experience under the preaching of Robert Semple. Semple had been born in Ireland, then migrated to the United States where he encountered some of the earliest Pentecostals. He was soon baptized in the Holy Spirit, spoke in tongues, and called to evangelistic ministry. In 1907 he led a “Holy Ghost revival” in the small town of Ingersoll, Ontario. Aimee attended, fell in love with Semple, and professed faith. She, too, had an experience of being baptized with the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, and being called to ministry. Aimee and Robert were married on August 12, 1908.

She went on mission to China. Robert felt called to China and Aimee went with him. On the way they stopped in the UK where Aimee preached her first sermon—for 15,000 people in Victoria and Albert Hall in London. They arrived in China in 1910. Aimee soon suffered a breakdown of some kind, and she and Robert both contracted malaria and dysentery. Robert died there on August 17, just two months after arriving. Aimee gave birth to a daughter, Roberta, on September 17, then returned to North America, eventually settling in New York. She soon met and married Harold McPherson whom, it seems, she never really loved. She and Harold had one son, Rolf. They would divorce in 1921.

Aimee became a traveling evangelist. One day Harold found Aimee had left with the children. She had begun a new life as a evangelist, and got started in her hometown. She quickly proved she could draw massive crowds and for the next seven years, until 1923, traveled all over North America preaching before thousands and tens of thousands. The media constantly covered her events and often reported on the miraculous healings they witnessed there. Through this ministry she became one of the most famous women in America and was often written about in the newspapers. Though she later reduced the emphasis on this healing ministry, she continued to perform healing services until her death.

She founded Angelus Temple in Los Angeles in 1923. Weary from the life of never-ending travel, and ready to establish a base, she founded Angelus Temple in Los Angeles where she preached 21 times each week. The church seated more than 5,000 and was often packed far beyond capacity. She called her brand of Pentecostalism the Foursquare Gospel since it was based on four cornerstones: Regeneration, Baptism in the Spirit, Divine Healing, and the Second Coming. Her most popular sermons at Angelus Temple were her illustrated sermons which were messages combined with props, music, acting, extras, and so on. Often lavishly produced, they were both entertaining and didactic.

She disappeared for 5 weeks. In 1926 Aimee disappeared for 5 weeks, then reappeared in Mexico saying she had been kidnapped and held prisoner in a desert shack. She always insisted this was the truth, though many people preferred to believe she had run off with a lover. The mystery has never been solved, despite being thoroughly examined from every angle by the media and a Grand Jury.

She saved lives during the Depression. During the years of the Depression she led her church to begin a Commissary which would distribute food, clothing, and other essentials without asking uncomfortable questions of those who requested the charity. In this way they fed over a million people. During other emergencies, such as great fires or earthquakes, she would mobilize her church and followers to respond quickly and generously.

She spent her final years under the control of Reverend Giles Knight. As time went on, her behavior proved so impulsive and embarrassing that those around her demanded she restrain herself. To this end, Giles Knight began in 1937 to control her private and professional life, and Aimee remained under his control until her death in 1944. Though she still preached, taught, and traveled, everything was under the watch of Knight. She would sometimes call another Foursquare minister late at night to cry that she was extremely lonely but not allowed to go out. Though she was productive in these years, she was often desperately unhappy. She was also regularly ill with a variety of illnesses and suffered a number of nervous breakdowns.

She rarely maintained relationships. She loved Robert Semple, but lost him after just two years of marriage. She married twice more, but neither marriage was happy and neither one lasted long. By the end of her life she had become alienated from her daughter Roberta and her mother Minnie (whose relationship with Aimee ended with a nasty lawsuit). She also had fallings out with Rheba Crawford Splivalo, who often preached at Angelus Temple when Aimee was unable or on the road, and with a host of other elders and church leaders. She had few, if any, friends.

She died of an overdose. McPherson died on September 27, 1944, after overdosing on sleeping pills classified as “hypnotic sedatives.” The pills had not been prescribed to her by a doctor and no one knows how she obtained them. Though some have speculated she committed suicide, there is no evidence of this and it seems more likely she did not know the proper dosage and simply took too many of them.

Aimee Semple McPherson is and was a troubled, troubling, fascinating figure whose fame and infamy made her an enemy to some and a hero to others. She remains an honored figure in Pentecostalism in general and in the Foursquare Churches in particular. There are now more than 76,000 Foursquare Churches across the world with more than 9 million members.

(Resources: Daniel Mark Epstein’s Sister Aimee makes for great reading, though he may be overly-reliant on his subject’s autobiography. It is probably the best place to begin in reading about her life. Smithsonian has a concise overview of her life and disappearance in “The Incredible Disappearing Evangelist.”)